Coming Soon

The new FON website is currently under development. In the meantime, we invite you to discover our current exhibitions and learn more about our partners, their works, and ways you can support their missions.

Current Exhibitions

FON’s Photographic Exhibitions connect people with nature through Hussain Aga Khan’s stunning images from global expeditions. These exhibitions inspire conservation action by showcasing the beauty and fragility of ecosystems and endangered species, raising awareness about biodiversity and climate change.

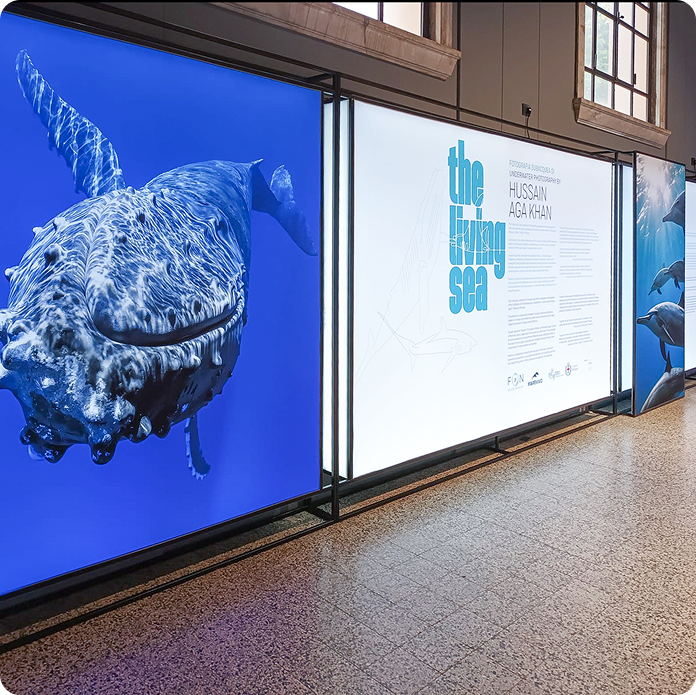

The Living Sea

From May 13th to September 5th

Natural History Museum Milan

Corso Venezia, 55,

20121 Milano MI, Italia

From 13 May to 5 September, Milan’s Natural History Museum will host The Living Sea, a photography exhibition by Hussain Aga Khan. The exhibition is the result of a collaboration between Marevivo ETS, the environmental foundation dedicated to protecting the marine ecosystem since 1985, and Focused on Nature (FON), founded by Hussain Aga Khan in 2014. This significant partnership is built on a shared commitment to marine conservation and to finding effective solutions to reduce ocean pollution.

The exhibition features 47 stunning underwater photographs by Hussain Aga Khan, photographer, storyteller, and environmentalist, offering museum visitors a captivating look into the extraordinary biodiversity of our oceans.

Fragile Ocean

From May 24th to July 6th

Cultural Space Lympia

2 quai Entrecasteaux,

06300 Nice, France

Through a selection of captivating photographs, Hussain Aga Khan invites visitors to explore the kaleidoscopic wealth of marine biodiversity observed off the Bahamas, Bora Bora and Moorea in French Polynesia, Costa Rica, Dominica, Egypt, the Galapagos Islands, Indonesia, Mexico, the Philippines and Tonga.

By capturing rare moments of intimacy with fascinating marine animals, these photographs testify both to the incredible beauty of the oceans and to the increasing fragility of their ecosystems, threatened by climate change, pollution and destructive commercial practices.

Partners

Turtle Conservancy

Jane Goodall Institute

re:wild

Whale and Dolphin Conservation

Wild dolphin Project

Wolves of the Rockies

Sheldrick Wildlife Trust

Shark Conservation Fund

Sea Turtle Conservancy

Rhino Pride Foundation

Oceana

Mission Blue

Manta Trust

Jocotoco Conservation Foundation

Jane Goodall Legacy Foundation

Fins Attached

Faune Alfort

Apex Protection Project

Wildlife Conservation Society

Maasai Wilderness Conservation Trust

International League of Conservation Photographers

Charles Darwin Foundation

Blue Marine Foundation

Looking for something specific from our old site?

Connect with Nature

Keep up with FON on Instagram for the latest photos and stories from Hussain Aga Khan’s expeditions and regular updates on events and partnerships.